Sales & Marketing Report 2017: The Progress Report

Over the eight years that CGT and IDC have presented this report, we’ve done our best to cover a similar set of topics from year to year. That not only lets us make year-to-year comparisons about how the industry is progressing toward universally accepted goals, it also lets us maintain a running narrative on the overall “state of sales and marketing” in the consumer goods arena.

That’s getting a little harder to do these days, however. Dramatic shifts in both consumer behavior and technological capabilities have changed those industry goals from, “How do we improve the way we do business today?” to the more alarming, “How do we transform the business for the future?”

Most of this transformation is, of course, taking place in the digital realm. It isn’t an exaggeration to say that digital technology has the potential to help businesses operate in fundamentally different ways, or to say that it can bring product manufacturers far closer to their customers and consumers than had previously even been imaginable.

As consumer goods companies continue to “become digital,” we are witnessing a transformational shift in the industry. IDC articulated this trend recently in a set of predictions that we believe will underpin the future of consumer goods:

1. Over the next decade, 90% of industry growth will be captured by companies that successfully engage directly with consumers. Consumers rule the world; they are ubiquitously connected, crave individuality/personalization, and are intolerant of complexity and latency. They are a consumer goods company’s worst nightmare — and its greatest opportunity. It seems intuitively obvious that the companies that figure out how to best engage with these consumers will get more than their fair share of growth. And, by the way, as older consumers give way en masse to millennials, the “problem” just gets worse.

2. As barriers to entry fall over the next five years, smaller “lateral” competitors will wrest 10 to 15 share points from traditional and established large enterprise players. Industry estimates find that, of the $35 billion in net growth over the past three years, only $1 billion has come from traditional, large enterprise players. Although small entrants historically have tended to contribute significantly to industry growth, I don’t recall the estimated share to ever be this high.

That’s an anomaly perhaps, but if you look at the ranks of new competitors to traditional businesses, they are appearing in record numbers. Part of the reason for this is that the historical barriers to entry (technology, manufacturing facilities, etc.) have fallen — they’re now either “commodities” or available via the cloud.

At an industry event a few years ago, I noted that anybody with “an idea and a garage” could launch a new venture; now, I don’t think you even need the garage. Another part is that, as consumers look for either personalized products or ones that appeal to their generation, smaller competitors are better positioned to be flexible and take risks.

3. By 2019, one-third of consumer goods companies will have benefited from digital transformation (DX), with the remainder held back by inflexible/outdated business models, processes or functional structures. IDC research finds that one of the biggest current gaps between digital “thrivers” and survivors is in the area of leadership. Only 29.6% of manufacturers have achieved a level of maturity in digital transformation leadership to reach the top two levels of “transformer” and “disruptor.” Leadership holds responsibility for creating a vision of where their companies are headed in the next decade, but most are not ready to change direction by adopting new business models or functional structures.

4. Not every company with a vision will be able to fully leverage its DX investments in the supply chain, since there are many dimensions to DX. But in the market, we can already see which supply chain leaders are laying out a roadmap for their companies to evolve in the next decade.

Look at Bayer’s move to join forces with Monsanto to increase its innovation in agriculture, or Under Armour’s investments in technology-enabled products and health information. These moves required executive leadership to recognize how both their business models and enabling processes must change — and not just incrementally, but fundamentally.

As we move rapidly into a world where the consumer is the primary moving force in the industry, consumer goods companies are going to have to answer some tricky questions.

For example, what happens to trade promotion funding in an omnichannel world? That’s not a big deal when direct-to-consumer sales are in the small, single digits, but what happens when they become 20% of total sales — or more? For a company that manages an annual trade promotion budget of $500 million, what happens to the $100 million that no longer supports traditional retail sales? Does it get converted to consumer promotion vehicles, taken to the bottom line as “savings,” or something else? In our discussions with consumer goods manufacturers, not many have a good answer.

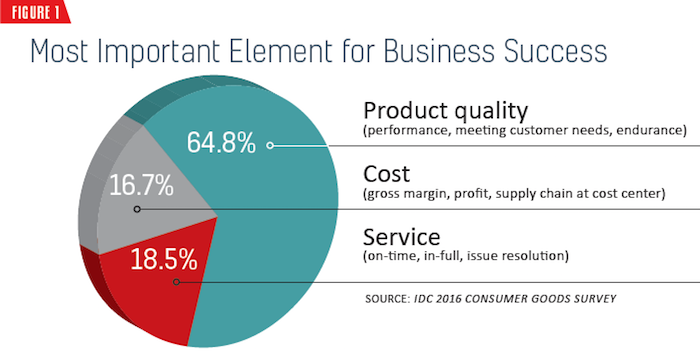

The other implication for consumer-centricity is that the focus of many businesses has shifted. While cost and service remain important, of course, the majority of companies now place the greatest importance on product quality. This shift has been happening for a few years but, as illustrated in Figure 1, almost two-thirds of consumer goods companies now cite product quality as most important.

The last two profound implications from our discussions with consumer goods companies are the nature of competition and the role of digital. If we accept the prediction above that, as barriers to entry fall, “lateral” competitors will wrest up to 15 share points from traditional players over the next five years, that will require those larger companies to change the ways in which they compete.

We’re already seeing growth in the industry accrue to small, nimble and often new competitors in the marketplace. Many of these competitors have been digitally enabled, with business models built on competencies that would not have been possible in an “analog” world.

Companies like Mink, for example, which use 3D printing as the basis for their product assortment and fulfillment, are able to meet the personalized needs of their consumers in ways that more traditional processes could not. We’re not saying that merely being digitally enabled ensures business success — in fact, it does not. But digital transformation is clearly a key element in being prepared for success.

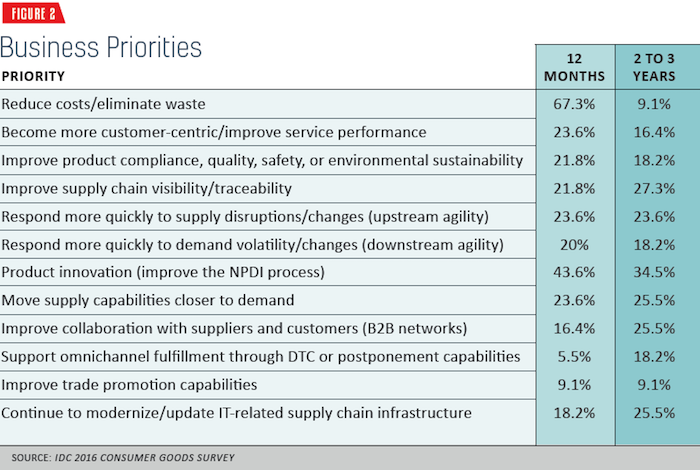

As we close this overview, it’s useful to check in with consumer goods company priorities for 2016 through 2019. As illustrated in Figure 2, we see something of a mixed bag of priorities. It’s true that in 2016, and continuing through 2017, cost reduction remains a top priority — although the presumption appears to be that opportunities for waste elimination will decline over time.

It’s interesting that things like customer-centricity and product innovation are listed as less important beyond 12 months. Perhaps companies believe they’ll solve these issues sooner, thus making them less of a future issue. If so, that is probably naive. There’s a clear future focus on collaboration (something that never seems to get “solved”), support for omnichannel fulfillment, and improving business and supply chain visibility. We’ll touch on these in the specific topic sections that follow.

_____________________________________________

To read the rest of the report, click on the links below:

- Sales & Marketing Report 2017: Editor's Note

- The Progress Report

- The Evolving Role of TPM

- What to Do with Data

- Is DTC the Future — or the Present?

- Taking the Risk Out of Digitization

- Building a Smart Digital Enterprise

To download the full report, click here.